By Kenny Paul Smith

In a recent post, I told the story of “The Young Women Who Was Visited By Her Dead Husband,” and referenced it as an example of “The Super.” Several folks have written in, asking for some clarification: “how does this relate to other categories, such “the paranormal,” “the supernatural,” “the magical,” and so forth. Great questions, which point us toward an interesting history.

Rewind to the 15th and 16th centuries, early-modern Europe. The Protestant Reformation was brewing. The Ptolemaic view of a flat-Earth-centered-cosmos was seriously challenged. Entirely new worlds and new peoples (i.e., the Americas) had been discovered, falsifying physical and cognitive mappings of the world that had stood for a thousand years. In essence, the foundations of the European civilization were crumbling. In this context of social upheaval, there was growing concern about human relationships with cosmic forces and powers, and teasing out which were religiously permissible and which were not.

Magic had always been part of medieval European culture. The term itself can be traced back to pre-Islamic Persia. There, the Magi served as astrologers to Persian emperors; it was their job to translate what the stars were “speaking” (literally, that’s what “astro-ology” means) and what this portended for decisions of state. Legends of such figures gradually began to appear in the European sphere, for instance, as the “wise men from the East” who, the biblical text suggests, followed the leading of a star to Bethlehem to witness the birth of the Messiah; and more broadly as the powerful, mysterious, and morally ambivalent figure of the Magus, who could read your fate written in the stars, and perhaps even rewrite that fate, for your good or ill.

But the medieval European world believed in different kinds of magics. There were natural magics, like astrology, which tracked cycles in the heavens and how they shaped events on Earth, but which were simply part of the world that God has created. There were also dark, demonic, black magics, like the practice of summoning the spirits of the dead, binding angels or demons in magical circles so that they might reveal secrets (e.g., where hidden treasure might be found!). By the 15th century, when official charges of “witchcraft” had both exploded in number and become primarily associated with women (more women were publicly executed between 1450-1700 for the crime of witchcraft than for all other crimes combined), religious authorities needed a conceptual and legal category for phenomena that wasn’t simply natural and wasn’t sordid human meddling with dark underworld powers. Enter the Supernatural, which referred to miraculous phenomena explicitly performed by God (e.g., the parting of Red Sea as told in the biblical text).

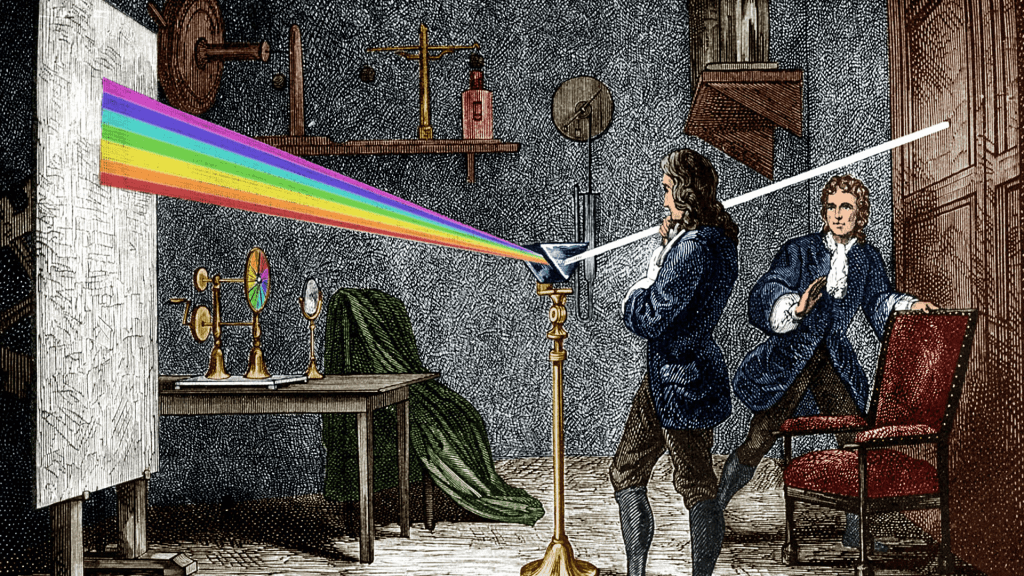

For centuries of European history, this was the taxonomical field of battle. When Sir Isaac Newton used a glass prism to split an incoming beam of sunlight into a spectrum of colors, for instance, there was great debate about what was at play in such events. Was this a miracle performed by God? Or something preternatural, that is, a feat performed by demonic powers to trick and deceive human beings into thinking it was God’s handiwork? Or was there something magical about the glass Newton used, or the room in which the ritual was performed, or was Newton himself a Magician or Sorcerer? Very few minds of the time embraced the “mechanical philosophy” to explain such events, which saw them as simply the result of predictable, mechanistic processes, entirely disenchanted.

Come the late 19th century. Western intellectuals in Europe and America were avidly studying all sorts phenomena that suggested that human consciousness survived the death of the physical body, such as deathbed visions, and trance and physical mediumship. They were not satisfied with the medieval taxonomy they had inherited, and so they coined a new interpretive category, the paranormal, to study phenomena and experiences that were well “above, beyond, or aside from, the normal” without being tethered to the assumption that some sort of transcendent deity was the cause.

Come the early 21st century. A growing number of scholars working in the broad field of the history of religions, agree that assuming paranormal experiences must always be reducible to fraud, exaggeration, deception, stupidity, lack of education, misperception, etc., because such events simply cannot happen, is vastly premature, and that the wiser course of action is to take a careful, evidence-based look at each and every account. At the same time, we are worried that terms such as supernatural and paranormal have been so thoroughly coopted by contemporary popular culture so as to be difficult to use with precision. Consider, for instance the wildly popular Netflix series, Supernatural, in the beloved Sam and Dean Winchester hunt down and destroy innumerable paranormal monsters, including demons, witches, Lucifer himself, rogue angels, vampires, werewolves, ghosts, ad nauseum. Or “reality” TV shows such as Paranormal State and Ghost Hunters. It’s fair to say that, like 15th century witch hunters and Victorian-era investigators of afterlife accounts, present day researchers need a new term.

Enter the Super, signifying any sort of experience that takes a human being well out of and beyond the normal, hinting at a vastly expanded understanding of reality, human potential and our collective future evolution. So, to answer the question with which this brief essay began, we are headed full steam into the Super in terms of the human beings who have such experiences and the scholars who study them. For a superb example of bothm, check out Jeff Kripal talk below.

Leave a comment