By Kenny Paul Smith

In Beyond Knowing: Mysteries & Messages of Death & Life from a Forensic Pathologist (2006), Janis Amatuzio relates a remarkable and, yes, mysterious case she worked on in her decades-long career as a crime scene investigator.

“As I started through the tunnel that connects the hospital and the professional building,” her tale begins, “I saw the hospital chaplain. Even from a distance he looked concerned. As his eyes me mine, he raised his hand and said, ‘I have to talk with you.’”

A young man, recently married, had died earlier that morning, when his vehicle rolled off the road into a ravine, and the concussive injuries he sustained ended his life. He had been working overtime shifts late into the night in order to save up money for a down payment on a home, had apparently fallen asleep on the drive home, and was found “in a frozen creek bed at about 4:45am.”

But the chaplain wanted to talk about something other than the forensic details, as the police had no doubt that the young man’s death, while tragic, was entirely accidental.

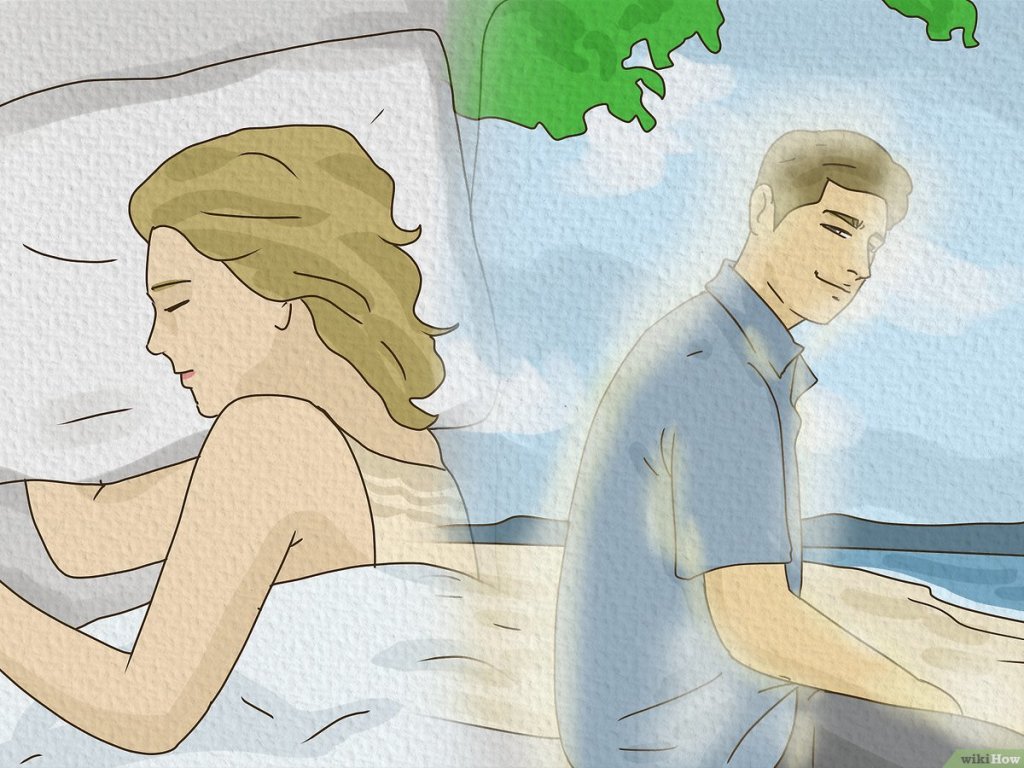

Apparently, at 4:20am that morning, the young man’s wife had been awakened from a terrible dream “in which her husband was standing by the bedside apologizing. telling her that he loved her and that he had been in an accident. She immediately called 911 and “with absolute certainty told the dispatcher her husband was in an accident not far from their home and that his car was in a ravine where he could not be seen from the road.”

What the young widow confided to the chaplain but not to the police was that “it didn’t really seem to be a dream. She said he was really standing there, next to the bed.”

How should we think about this woman’s experience? With my own disciple, the Academic Study of Religion, many would quickly point out that her experience was inherently religious, meaning that it dealt matters of ultimate concern: life, death, love and connection. Within the broader Humanities, Social Sciences, and STEM fields, scholars of all sorts would likely emphasize the ways in which such dreams help us to cope with the trauma and loss, and that’s why human beings, from every culture of which we have records, contains reports of such experiences. These are valuable interpretive moves, and tell us something important about being human. For, we are forced to cope with loss, and we do suffer greatly when we loose someone with whom we are building a life, so it should be no surprise that the complex depths of the human being find all sorts of ways to help us heal and move on, even to the point of the imagination creating dream-encounters with departed loved ones.

But there is something crucial missing from this sort of readings, namely, how did the young woman know what had happened to her husband and where his body could be found? Remember that she called 911 twenty-five minutes before the police had been dispatched to search for, and ultimately located, his flipped-over vehicle and body within, and that the young women was not found to have had anything to do with causing this terrible event. As academic disciplines are currently configured, it is precisely this sort of question that is brushed aide. Should one push on this point, the most likely response would be, ‘there must be something amiss in the story itself, because such things are simply not possible.’

Enter the Superhumanities. This currently emerging field does not assume that any experience or phenomena are impossible. Rather, it collects all sorts of accounts and works to separate out what is purely subjective and what, if anything, suggests an objective connection with something empirically real. There certainly is something objectively real in the powerful, subjective experience the young woman in the story above report: knowledge that she could not have possessed but did. If you’d like to insist that this sort of thing is impossible, that’s fine. As Jeff Kripal, who coined the term “The Superhumanities” on the basis of his own research puts it, ‘These things are impossible, but they happen, a lot.’

As it turns out, the concept impossible is entirely relative to one’s worldview, which is powerfully shaped by one’s place in cultural and history. Obviously, all sorts of things modern day human beings take for granted would have been demarked as “impossible” in previous centuries, or even decades.

Here’s why this matters. If “vanilla” scholarly frames tell us something important about being human, this is exponentially greater in the presently emerging Super academic disciplines, which pursue the most venerable and most important questions in all of human history, and do so in ways that do not rule out in advance what the answers can be.

Leave a comment